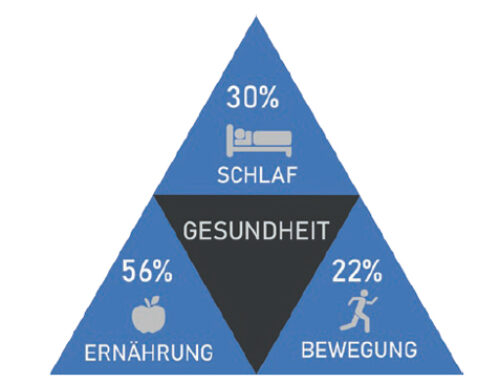

Sleep and immunity

Mikhail G. Poluektov, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Sleep Medicine, Department of Neurological Diseases and Neurosurgery, Sechenov University, Moscow, Russia

In the era of the COVID-19 pandemic, the absence of proven remedies to prevent or effectively treat this disease raised the need for natural factors providing optimal functioning of the immune system. In experimental animals that died due to complete sleep deprivation, septicemia was considered a feature of immune defense depletion.

Changes in the humoral and cellular parts of immune system that occur in the state of sleep are diverse. A detailed analysis of this topic is excellently reviewed by L. Besedovsky et al. (2019) [1]. As noted by the authors, the most important feature is the migration of immunocompetent cells during sleep from the peripheral blood to the regional lymph nodes. Here the naive lymphocytes are trained to recognize new threats after the contact with the antigen. The activity of NK cells was also shown to increase during sleep, while sleep deprivation leads to a decrease in their number. With regard to the humoral part of immunity, the production of proinflammatory cytokines (interleukins 1 and 2, TNF-alpha) decreases during sleep and increases with sleep deprivation. The ratio of pro-inflammatory / anti-inflammatory cytokines shows similar trend in sleep.

The practical consequence of these changes in the immune system is the alteration of the host defense after sleep duration shortening. In a study by A. Prather et al. (2015), 164 healthy volunteers were inoculated with rhinovirus containing nasal drops. The susceptibility to the disease was 4.24 times higher in subjects who slept for 5-6 hours than in those who slept for 7 hours or more [2]. The behavioral reduction in sleep time on weekdays is an emerging problem in industrial society. Daytime sleep can be considered as a measure to reduce the risk of impaired immunity due to the incomplete sleep deprivation [1]. Not only a reduction in sleep time, but also a violation of its quality, can also affect the resistance to infection. In a study by A. Donners (2015), Dutch students were asked to fill out the sleep disorders questionnaire SLEEP-50 and describe their own health status [3]. Indeed, the improvement of sleep in insomniacs undergoing cognitive-behavioral therapy was accompanied by a decrease in circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and C-reactive protein [1]. In light of the spreading mass vaccination, it seems relevant to prove the positive effect of sleep on the parameters of the acquired immune response. K. Spiegel et al. (2002) showed 2.5-times higher antibodies levels in subjects adhering to a normal (7-8 hours) sleep schedule compared to those who slept for only 4 hours [4]. In the near future, results of the effect of sleep duration on the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination should be manifested. Obviously, the severe epidemiological situation along with an undoubted negative impact will bring new knowledge about the nature of mysterious and still promising state of sleep.

- Besedovsky L, Lange T, Haack M. The sleep-immune crosstalk in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(3):1325–80. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00010.2018

- Prather AA, Janicki-Deverts D, Hall MH, Cohen S. Behaviorally Assessed Sleep and Susceptibility to the Common Cold. Sleep. 2015;38(9):1353–9. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.4968/

- Donners AAMT, Tromp MDP, Garssen J, Roth T, Verster JC. Perceived Immune Status and Sleep: A Survey among Dutch Students. Sleep Disord. 2015;2015:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/721607

- Spiegel K, Sheridan JF, Van Cauter E. Effect of sleep deprivation on response to immunizaton. J Am Med Assoc. 2002;288(12):1471–2. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.12.1471-a

Subjects who perceived themselves as having reduced immune functioning had the worst subjective sleep scores and higher scores associated with insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, and circadian sleep rhythm disorders.